| One of the skills that separates novice photographers

from the more experienced is an awareness and control over “Depth

of Field” (commonly referred to by its abbreviation “DOF”).

Sometimes, to get the shot, we need to use a very small aperture. When

we do, not only is the subject in sharp focus, but features in the background

and/or foreground can compete for attention. This tutorial will walk

you through the steps in using a new feature in Adobe Photoshop CS: the

Lens Blur filter.

If you take an image where the subject is at a distance, everything

in the image at that same distance will be equally sharp. Features

in front or behind the subject will have less sharpness. The further

they are from the subject, the less sharp. DOF is the zone of acceptable

sharpness that extends in front of and behind a sharply focused subject.

Figure 1. Too much DOF allows leaves and stems to compete for attention

with this

White Iris bloom.

There are three basic facts to DOF. Holding everything else equal:

• DOF increases as a lens is stopped down (i.e., the f/number

is increased);

•

DOF increases as focal length decreases;

•

DOF increases with subject distance.

Experienced photographers attempt to manipulate these factors in order

to control how much of the background and foreground blurs and how

strong the blur will be. There are images that should be sharply focused

throughout. Landscapes are usually shot with tiny apertures like f/11

and f/18 to have everything in focus from a few feet in front of the

photographer all the way to the horizon. At other times, a blurred

background or foreground is preferred. When you take a macro or near-macro

shot, the DOF can be as small as a fraction of an inch. Make a mistake

and either the front or the back of your subject will show evidence

of being out of focus.

The image in Figure 1 is one of those situations where DOF works against

you, where a sharply focused subject means competing features in the

background or foreground will also be brought into relative sharpness

and detract from the subject.

I had to choose. Did I want a blurry background in order to keep the

eye on the flower bloom? Did I want every feature on that flower bloom

to be in relatively sharp focus? The physics of the situation – 180mm

macro lens, Canon 10D, the size of the bloom, my distance from the

bloom (1.5 meters) – all required that I use a small aperture

in order to get the iris blossom in sharp focus. I used f/32 at 1/10

of a second on a sunny day.

f/32? What about diffraction? Fortunately, I was using a Canon 180mm “L” macro

lens. If you have never used one, the quality of the optics will astonish.

Even at minimum aperture, this lens delivers sharp, crisp images.

I would have preferred to back off to something like f/22, but my

DOF would have narrowed so much that features of the iris blossom would

lose sharpness. Even at f/32, the DOF extended a scant 2 inches. At

f/22, DOF would extend less than 1 ½ inches. Not enough. I stood

back at 1.5 meters, rather than allowing the blossom to fill the viewfinder

in order to extend the DOF a bit.

When I am out in the field, I do not calculate DOF with such precision.

I instead use the DOF preview button and run my eye over the subject.

Especially the petal edges in this case. The problem you confront with

the DOF preview is viewfinder brightness. The viewfinder is very dim

at f/32, even on a bright, sunny day. I bracket for DOF in that circumstance.

For this shot, I bracketed f/22, f/25, and f/32.

I knew from the DOF preview that the background was going to be a

challenge. The iris blossom was in the middle of a bunch of leaves

and stems. Some were the same distance from the lens as the subject.

They were not going to blur sufficiently. The solution was to rely

on isolating and blurring the background in Photoshop.

Using the Lens Blur Filter

Photoshop CS added the Lens Blur to the Filter | Blur menu items.

In prior version of Photoshop, you would instead use Gaussian Blur

to

give the appearance of a narrower DOF to an image. The Lens Blur

filter adds a more realistic blur. It is also a more complicated

filter to master.

To use the Lens Blur filter, you need to be comfortable making selections

and converting selections to masks. The Lens Blur effect relies on

a Depth Map to control which features get blurred and how much blur

is applied to them relative to other image features.

Figure 2 is the same White Iris in Figure 1. The image was cropped

from a 2:3 aspect ratio to a 4:5 aspect ratio. Cropping removed some

of the leaves and stalks, enhancing the white blossom.

Figure 2. Effective cropping enhances the subject.

The background in Figure 2 is still distracting -- especially the

leaf at 5 o’clock pointing straight at the blossom. The first

step in using the Lens Blur filter is to create a Depth Map. A Depth

Map is just a grayscale image. Typically, an alpha channel. If you

recall that white reveals and black conceals with a mask, then black

protects features from blurring (i.e., black conceals features from

the Lens Blur effect), white permits the full effect of the blur, and

shades of gray progressively allow more/less of the blur effect.

I started by duplicating the Blue channel. There was already a lot

of contrast between the flower and the background.

Figure 3. The Blue channel was a good place to begin crafting a Depth

Map.

I used the Magic Wand to select the background, making sure the Contiguous

box was checked on the Option Bar. This kept the selection away from

the darker details on the flower itself. Using a Tolerance of 30, it

took all of a half-dozen clicks of my Wacom tablet pen to select the

entire background. I then converted the selection into an alpha channel

by selecting the “Save selection as channel” icon at the

bottom of the Channel Palette.

To soften the edge of the selection, I applied a 1 pixel Gaussian

Blur to the new mask. This left me with a well-defined mask for the

flower. I had my Depth Map.

Figure 4. Mask of the flower to be used as a Depth Map for the Lens

Blur effect.

To repeat, where the mask is black, there will be no blur applied.

Where the mask is white, the image will receive the full blur effect.

Shades of gray would receive a corresponding amount, with brighter

tones receiving more blur than darker tones.

I used the Magic Wand for this example. You can use other selection

tools, too. Gradients can be very helpful for reducing DOF in a way

that adds a dream-like or romantic aura to an image.

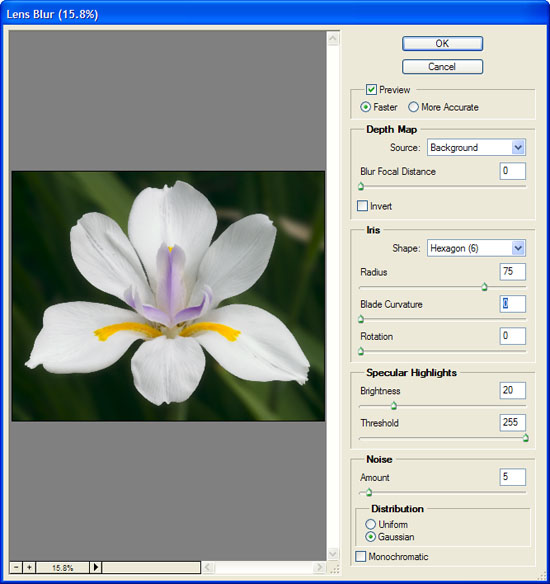

Once you have your mask ready, select Filter | Blur | Lens Blur. A

dialog window will open. You can toggle the preview on and off by selecting

and unselecting the Preview checkbox.

Be warned! The Lens Blur filter is performing lots of very complex

calculations. It can take a minute or two on even the fastest workstation,

especially if you select the More Accurate option for the preview.

Figure 5. Settings for blurring the background with the Lens Blur

filter.

The setting for Blur Focal Distance determines the depth at which

pixels are completely in focus. I left it at 0, which provides the

behavior mentioned earlier: black areas in the Depth Mask are completely

in focus, white areas are completely blurred. This is ideal for an

image, like the White Iris, where there are no foreground features

to blur.

When you have both foreground and background to blur, you could instead

set Blur Focal Distance to something like 128. A setting of 128 is

convenient because in that case, 50% gray pixels would be completely

in focus and pixels lighter or darker that 50% gray would receive progressively

more blur as they vary from 50% gray. This is very helpful when using

gradients as a Depth Mask. If you prefer, you can click on the preview

and the Blur Focal Distance slider will match the location you clicked,

setting that depth as in-focus.

The appearance of the blur depends on the settings you choose for the

Iris parameters. This is what distinguishes the Lens Blur filter effect

from the Gaussian Blur effect. Radius for the Lens Blur filter corresponds

to the Radius setting for Gaussian Blur. It determines how pronounced

the blur effect will be. Choosing a different shape for the iris, a

different number of blades, and the curvature of the blades will result

in a different blur pattern.

Macro photographers refer to the blur of a lens for features outside

the DOF as “bokah.” Lenses with a pleasant background blur

are highly prized. The Lens Blur filter lets you dial in a desired

bokah.

Another distinguishing characteristic of the Lens Blur filter is the

settings for specular highlights. This gives added reality to the blur

effect. Out-of-focus specular highlights do not blur in the same way

as less pronounced features. The shape of the iris has an especially

strong impact on how specular highlights blur.

Figure 6. The same image after the Lens Blur filter.

Blurring an image will smooth the effects of luminosity noise. Those

are the grainy, splotchy effects from digital cameras that are especially

noticeable in the shadows and areas with color gradients, like large

areas of blue sky. The image will look more realistic if you add back

some random noise. If you experience chromatic noise as well, you can

select the Monochromatic checkbox to prevent the noise from affecting

the color of your image.

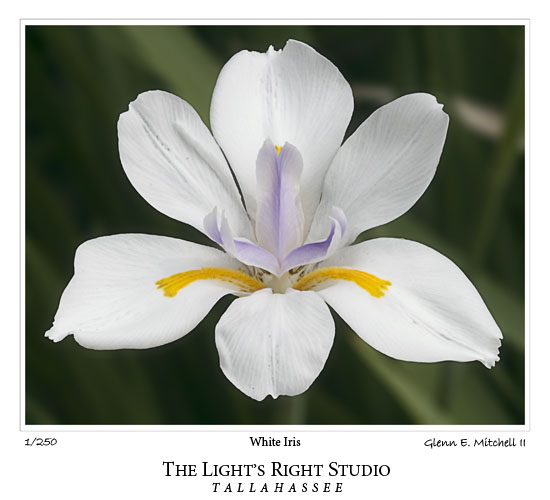

Figure 6 shows the result of the settings in Figure 5. The background

now recedes. Attention focuses squarely on the White Iris. The bokah

is pleasant and realistic. All that remains is to sharpen a bit and

finish with a frame effect.

Figure 7. Pretty as a picture after a touch of Highpass Filter sharpening

and a gallery

frame edge effect.

Figure 7 is the result of Highpass Filter sharpening with a Radius

setting of 6.5 and a gallery frame effect I learned from Scott Kelby,

President of the National Association of Photoshop Professionals (NAPP).

Concluding Comments

I do a lot of botanical and nature photography, so I constantly wrestle

with getting just enough DOF to blur the background without losing

sharpness at the tips of flower petals or on stamens projecting

out towards the camera on long antlers. Sometimes I get the shot.

Sometimes

I wind up with less DOF that I would have preferred. I usually

hedge my bet by bracketing my shots.

The Lens Blur filter changes all that. I can shoot for wider DOF to

make sure I get all of the flower details in focus and then narrow

the DOF once I get the image loaded into Photoshop CS.

Narrowing the DOF in a realistic way begins with the careful creation

of a Depth Map. Once you have struggled to get your subject totally

in focus, you do not want to lose any of it. You want to limit where

the effect is applied. You also want to the focus to change as your

eye approaches or recedes from the subject. So, you need to be comfortable

with selections and channels to make effective use of the Lens Blur

filter.

You can create background and foreground blurs with the Gaussian Blur

filter. The real power of the Lens Blur filter is the way in which

it mimics the changes an image undergoes as the lens barrel twists

from sharp focus to out-of-focus.

You have a lot of control over the blur effect. Different choices

for the iris shape, number of blades, and curvature of those blades

allows you to affect the bokah in subtle (or not so subtle) ways. You

can especially tell the difference in how specular highlights are treated

compared with using a Gaussian Blur.

To keep the effect realistic, keep in mind that DOF does not typically

extend equally in front and behind the subject. Macro and near-macro

shots come close to 50:50. For most photographic subjects, the zone

of acceptable sharpness will typically extend twice as far behind the

subject as it will in front of the subject.

|