Notes by Uwe are in italic.

All photographers know that perfect light is rare. There are two

main lighting situations for nature and landscape photographers:

a) strong sun

b) cloudy or overcast

The perfect light often would be a very, very light overcast like

a huge soft box. If the sun is strong digital cameras hardly can

master the dynamic range of the photo. In overcast the image tends

to

be to flat and also lacks the brilliance the sun light can provide.

We personally try to photograph in overcast as the California

sun is hard to master. That is why we like that Mitch covers the

topic how to get the best out of your overcast shots.

Let’s begin our discussion on improving problem images with

a look at a typical problem image. The photo to the left was taken

at the Linn of Dee in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. My wife and I spent

a week in Scotland during May and the weather was against us. The

weather was rainy and dreary.

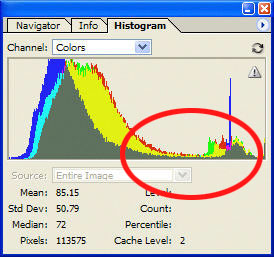

Figures

1a and 1b. A “low key” photograph and its histogram.

The histogram in Figure 1b tells the tale here. Nearly all of the

pixels in the image are dark tones. A few shadows and middle tones:

predominantly three-quarter tones. Few pixels are brighter than middle

gray.

Histograms are graphs of the pixels in an image. They plot the tone

of the pixel, from dark to light (left to right) on the x-axis and

the number of pixels with that tone on the y-axis. Histograms in Photoshop

also contain other useful information. For example, the median value

for the image is 72. Half of the pixels in the image will be lighter

than the median and half

will be darker. Since the individual data values in any RGB image can

range from 0 to 255 (black to white), a median value of 72 means half

of the information falls in the three-quarter tones and the shadows.

This is consistent with the somber colors we see in the image.

The term of art for an image with a large clump of dark pixel and

few bright pixels is low key. Low key images tend to look dim, flat,

and uninteresting. They are sometimes described as muddy. This picture

of water shooting through the rocks should be inspiring.

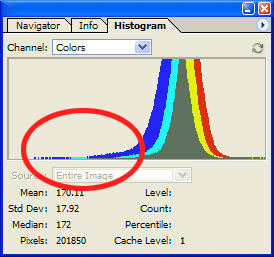

The opposite is evident in the histogram for the image of a freshly

molted ghost crab. The crab is hard to distinguish from the sand and

shell fragments on the beach. Wonderful camouflage for the crab, but

it will be a challenge to make the crab stand out against the background.

Figures

2a and 2b. A “high key” photograph and associated

histogram.

Nearly all of the pixels are brighter than average. A few middle tones

and lots of one-quarter tones and not much else. The median of 172

indicates that one-half of the information is in the quarter-tones

and highlights. High key images often appear washed out rather than

muddy. The effect is again a dull and uninspiring image.

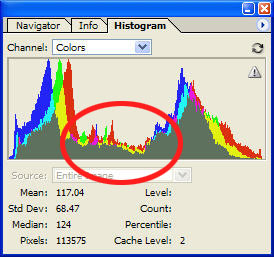

Sometimes an image can have lots of information in the highlights

the shadows and still appear dull and muddy. Dreary, overcast days

can drain an image of middle tones. You need more than high contrast

to make an image interesting. Just look at the image from the Bay of

Firth, Scotland in Figures 3a and 3b.

Figure 3b has plenty of what we look for in an image: plenty of tonal

range, plenty of contrast between shadows and highlights, plenty of

saturated colors. What the image does not have plenty of is “pop.” The

highlights would improve with a bit of careful brightening, but it

is those flat middle tones drain all of the interest from the image.

Figures 3a and 3b. Flat midtones can leave the interest for an

image equally flat.

Getting Our Terms Straight

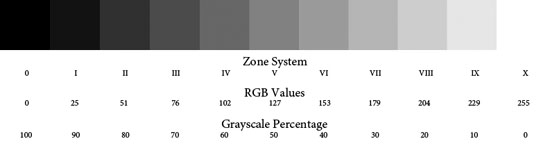

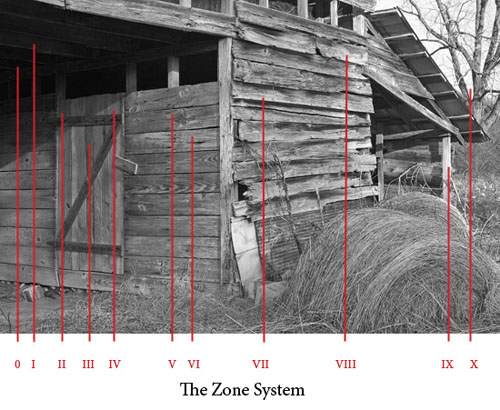

Ansel Adams codified his Zone System in the 1940s. It divides an

image into 11 zones. Sometimes his zones are referred to as tones,

although

it would be more accurate to say each zone is a discrete range

of tones. (See especially, The

Negative by Ansel Adams)

Zone 0 is the darkest shadows: maximum black with no evident detail.

Zone X is the brightest highlights: white with tone but no evident

detail. Zones I through IX represent tones with detail, going progressively

from very dark to very light.

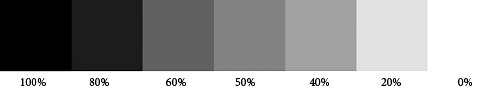

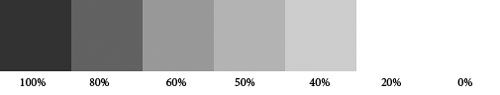

Figure 4. A grayscale wedge with corresponding values

Zone V is middle gray (127 in RGB, 50% in grayscale). It was the key

measurement in Ansel Adams’ Zone System. Zone V represents

normal tones under normal lighting. With film photography, you typically

set the exposure so middle tone objects are exposed according to

the meter. If you need to preserve highlight detail, you compensate

by subtracting stops or reducing the length of the exposure. This

keeps the highlights from “burning out” and reduces the

brightness of the rest of the image. If “stopped up shadows” was

the likely result, you added stops or lengthened the exposure. This

increased brightness not only for the shadows but for the rest of

the image as well.

With typical camera metering and auto exposure, the subject is rendered

as a middle tone. A brighter than middle tone subject will be darkened

unless exposure compensation is applied. Highlights, like snow can

become a dingy gray, without positive exposure compensation. Darker

than middle tone subjects need negative exposure compensation to avoid

lightened shadows.

Figure

5. The zones identified in a B&W image.

Ansel Adams urged photographers to previsualize how the photograph

will appear prior to making an exposure. This forces the photographer

to be deliberate during exposure.

While digital photography can still benefit from many of Ansel Adams

insights, the way light affects photoreceptors on a CCD or CMOS imaging

chip is not the same as how light affects photographic emulsions. This

is especially evident in Ansel Adam's advice, "Expose for

the

shadows and develop for the highlights." Michael Reichmann argues

that with digital photography it is important for photographers to

expose for the highlights and develop for the shadows. "Expose

to the Right" ensures

the best signal-to-noise ratio.

I find that you have to use the Expose to the right very, very

carefully. Read my article "Watch

your Histogram"

Film photographers, especially slide film photographers, are accustomed

to underexposing images to increase saturation and avoid burning out

highlights. Digital photographers have one enormous advantage unavailable

to film photographers (unless they shoot Polaroid film). Digital SLRs

provide the photographer with immediate visual feedback about their

shot.

I am not referring to the tiny LCD preview of the image. Lighting

in the field and LCD displays do not mix well, especially when trying

to make fine determinations about exposure. Digital SLRs and the better

digicams also provide a histogram of the exposure values, and those

histograms are a critical tool for “postvisualizing” your

digital images while out in the field. If we stick to Ansel Adams meaning

of previsualization, which occurs before exposure, then postvisualization

is the process of imagining how the image will appear once we get back

from the field and start to work with it in our image editing software.

Did we expose correctly? Do we need to shoot again?

With Expose to the Right (ETTR), you aim for a histogram that approaches

the right edge of the histogram but does not clip any highlights. You

are exposing for the highlights.

Previsualization is an essential step for most DSLRs and digicams

when using ETTR. Current digital cameras typically measure only average

luminosity for the three channels rather than displaying each channel

individually. It is therefore possible to clip a single channel and

see no evidence on the histogram or a highlight warning. So, care is

required in the application of the technique: especially with highly

saturated colors in bright light. You either need to back away from

the right a bit or bracket your exposures.

ETTR is a technique that brightens the image. This is critical for

reducing noise in digital images. While CCD and CMOS imagers are linear

devices over most of their operating range, noise is a common problem,

especially in deep shadows. Slight differences in sensitivity among

the photoreceptors become increasingly noticeable under low light conditions.

If you magnify the shadows of many digital images, you will see evidence

of luminosity noise. It is sometimes described as blotchiness

ETTR reduces noise, but once you have exposed for the highlights,

you then need to develop for the shadows. This is done during photo

editing, typically through adjustments to tonal range, contrast, and

brightness.

Figure 6. Reduced tonal range typically results in a flat, dull image.

Dynamic range is the difference between the darkest tone that a photographic

medium can capture and still hold detail and the lightest tone that

can display detail. To capture detail, tones need to be distinct.

The left half of Figure 6 above shows less tonal range than the right.

The tonal range of a particular image is just the numeric difference

between its maximum highlight and its minimum shadow. Extending the

tonal range makes the darkest pixel darker and the lightest pixel lighter

and moves all of the intermediate pixels corresponding amounts to fill

out the new tonal range. Details in the sand stand out more from the

background as a result of a quick adjustment in Photoshop with the

Levels control. The starfish has more “pop.”

There are exceptions, like the black cat in a cave or a polar bear

on the snow, but having a full tonal range is generally a good thing

for photographs. The darker the darkest areas, and the brighter the

brightest areas, the more contrast the image will have. A full tonal

range ensures that the image has the fullest possible overall contrast.

Images that are almost exclusively highlights and/or shadows, while

posing special challenges, are the exception.

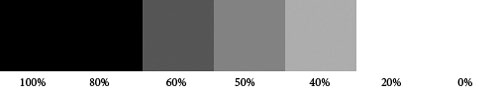

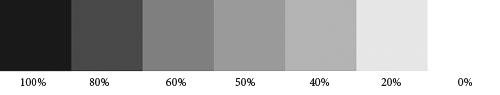

Figures

7a – 7c. A grayscale wedge before/after contrast adjustments.

Contrast is a related concept. When you increase contrast, dark pixels

become darker and light pixels become lighter. Middle gray is unaffected.

Since the human eye finds details by looking at differences in luminosity

and color, increasing contrast nearly always makes fine details more

evident.

Figures 7b and 7c show the result of increasing contrast to a grayscale

wedge. This was done with the Photoshop Brightness/Contrast control.

Figure 7b is the result of a +20 increase made to the Contrast slider.

Notice how the 80% patch has darkened and the 20% patch has lightened.

Figure 7c is more extreme: a +40 increase to the Contrast slider. Both

the 80% and 20% tone clipped. The 80% tone became indistinguishable

from the 100% tone, and the 20% became indistinguishable from 0% tone.

It is also important to notice that the 60% and 40% tones were only

slightly affected by even the aggressive +40 contrast adjustment. The

tonal range for the image would remain exactly the same. Lighter shadow

tones and darker highlight tones tend to disappear when contrast adjustments

are overly-aggressive. This causes the highlights and shadows to posterize,

leading to a loss of detail.

Controlling contrast is critical to image editing. For an image to

appear life-like, it must contain a wide range of brightness values.

Place two versions of the same image side-by-side, most people will

prefer the print with higher contrast.

I learned from Thomas Knoll that it is just a fact that if you

watch the same image with different contrast the higher contrast

image will always grab your attention. That does not mean it is always

better. In figure 6 (excellent example) the optimum may be somewhere

in the middle. Look also at you image by itself and not only in comparison

to stronger contrast variations. Also keep in mind whether your printer

can even handle the contrast of your image. We mostly print on matte

papers and here the contrast is limited by the paper itself.

Brightness is another related concept. When you adjust brightness,

you affect every pixel equally. When you increase brightness, all of

the pixels lighten – dark and light pixels alike. Highlights

can clip, if you are careless when increasing brightness. When you

decrease brightness, all of the pixels darken. Shadows can stop up

when decrease in brightness is extreme.

Figures 8a -8c. A grayscale wedge before/after brightness adjustments.

“Linear” is the jargon for a change that affects every

pixel in the same way. Brightness takes the existing histogram and

slides it to the right when brightness is increased and to the left

when brightness is decreased. “Nonlinear” changes affect

some pixels more than others. They compress some of the information

displayed in a histogram and/or expand some of it.

All of the pixels in Figure 8b brightened, except for those that were

already 0%. Those pixels had no additional values to assume. They were

already at maximum brightness. The Brightness slider was set at +25.

Figure 8c has clipped highlights. A more aggressive +50 setting for

the Brightness slider caused the 20% tones to clip completely. Once

highlights (or shadows) clip, their information is lost forever. You

can move a wide range of pixels to 255, but they will move back from

255 as one large clump. Clipping compresses all of their previous information

into one single value. Protecting highlights and shadows from clipping

is an important consideration when adjusting tonal range, contrast,

and brightness.

Where Do We Go From Here?

When faced with a dull, muddy picture, you might be tempted to reach

for the Brightness and Contrast control. Most pros advise against its

use altogether. I tend to agree. The only time I can recall using them

is the simple adjustments for this tutorial. They are not part of my

digital workflow. The Levels and Curves tools give you more flexibility.

Not only can you adjust brightness and contrast, you can also adjust

the overall tonal range, middle tones, color balance, and even adjust

the highlights separately from the shadows.

The rest of this tutorial series will explore the wide range of options

in Photoshop CS for handling problems with tonal range, contrast, and

brightness. The next tutorial will discuss the features in Adobe Camera

RAW II for making basic adjustments to tonal range, contrast, and brightness.

|